Basic Science Research

The physician-scientists in Weill Cornell Medicine's Division of Cardiology are engaged in a wide range of basic science research. As it relates to the pressing questions in the field of cardiology, studies focus on cell biology, immunology, biochemistry, pharmacology, and genetics from bacteria to humans.

Weill Cornell Medicine offers a variety of services and development programs to support the success of scientists and investigators at all levels. The Division of Cardiology offers an integrated and collaborative environment where basic science research is highly valued.

Past Reserach

Dr. Bruce Lerman: Genetic Origins of Idiopathic Ventricular Tachycardia

Dr. Bruce Lerman

Ventricular tachycardia (VT) is a potentially life-threatening rhythm disorder of the heart. While there are several different causes of VT, about ten percent of patients have no apparent structural cardiac abnormalities, in what is called “idiopathic” VT. In the most common form of idiopathic VT (RVOT), patients have no family history of VT.

Research conducted under the leadership of Weill Cornell Professor of Cardiology, Bruce Lerman, since the 1980s has suggested that RVOT is caused by a mutation in the gene for a protein called Gsα, and indeed such a mutation has been discovered in cardiac cells in Dr. Lerman’s laboratory. This is surprising, because in general the cells of the heart, unlike other organs where this mutation is found, do no continue to grow and divide after adulthood.

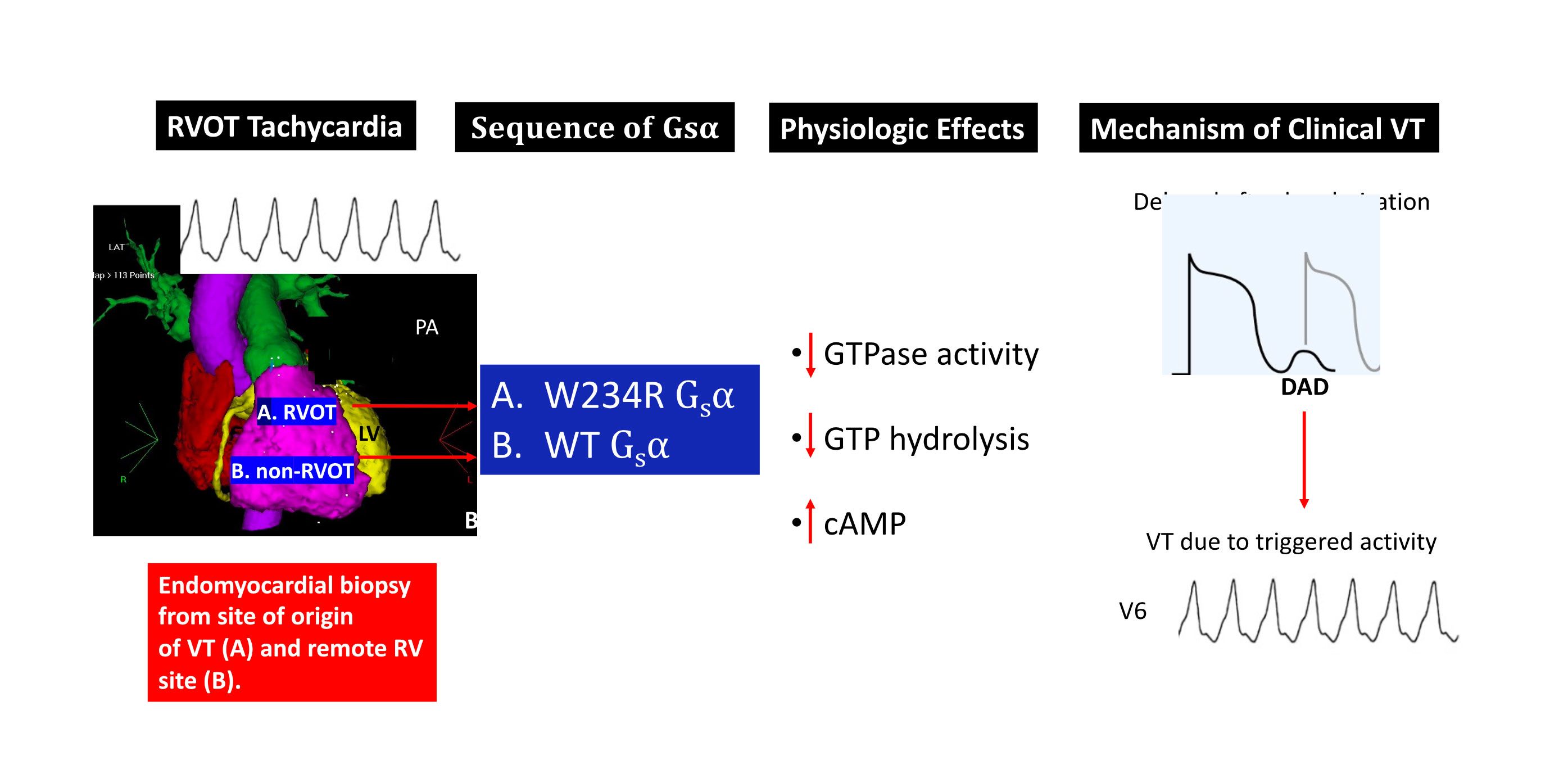

Current research, funded by the Kenny Gordon Foundation, has focused has on the cellular and molecular bases for “idiopathic” right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT) tachycardia. Although genomic mutations have been identified in ion channels and structural proteins that cause some of the less common forms of ventricular arrhythmias, the etiology often remains elusive for the most common form of idiopathic VT, that which originates from the RVOT. We have previously shown that RVOT tachycardia is caused by cAMP-mediated intracellular calcium overload that gives rise to delayed afterdepolarizations and triggered activity. Our work has also highlighted the contribution of somatic mutations to clinical cardiac disease, and demonstrates that VT, in particular, may be caused by cardiac somatic mutations in signal transductions proteins. Specifically, we have shown these arrhythmias are related to myocardial somatic mutations in the genes that encode Giα and A1AR, and GNAS, the gene that encodes the stimulatory G protein Gsα, all of which regulate intracellular cAMP. These mutations are only identified at the site of focal myocardial origin in the RVOT. Myocardial biopsies at other sites do not show the mutation, consistent with a somatic mutation rather than a germline mutation.

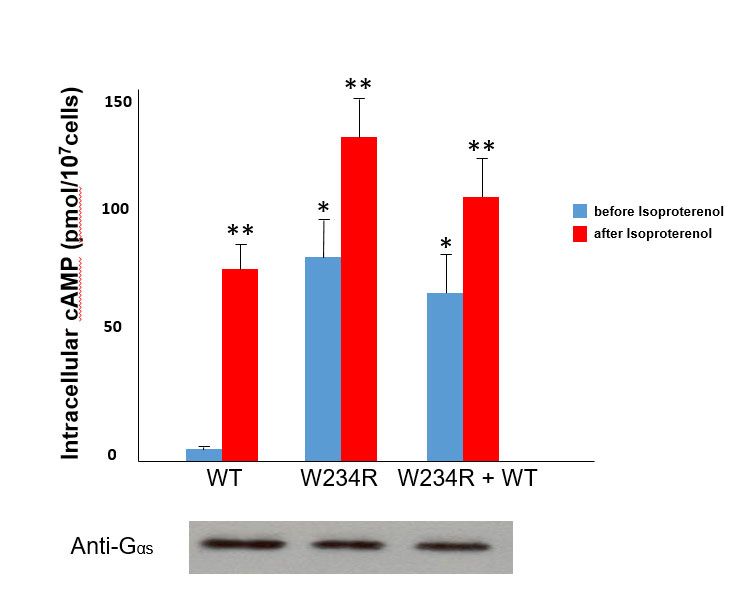

To illustrate one example, functional studies of mutant G234R Gsα (identified from a patient with RVOT tachycardia) showed a marked increase (approximately 16-fold) in basal levels of cAMP compared to cells transfected with wild-type Gsα. Moreover, the basal levels of cAMP of mutant Gsα approximated adrenergically-stimulated (via isoproterenol) levels of cAMP in wild-type Gsα transfected cells. These findings therefore suggest that the somatic mutation obtained from the site of VT origin constitutive activation of Gsα (see figure).Gsα and structural modeling predicted that the W234R mutation causes GTP binding in a conformation unsuitable for hydrolysis (figure below).

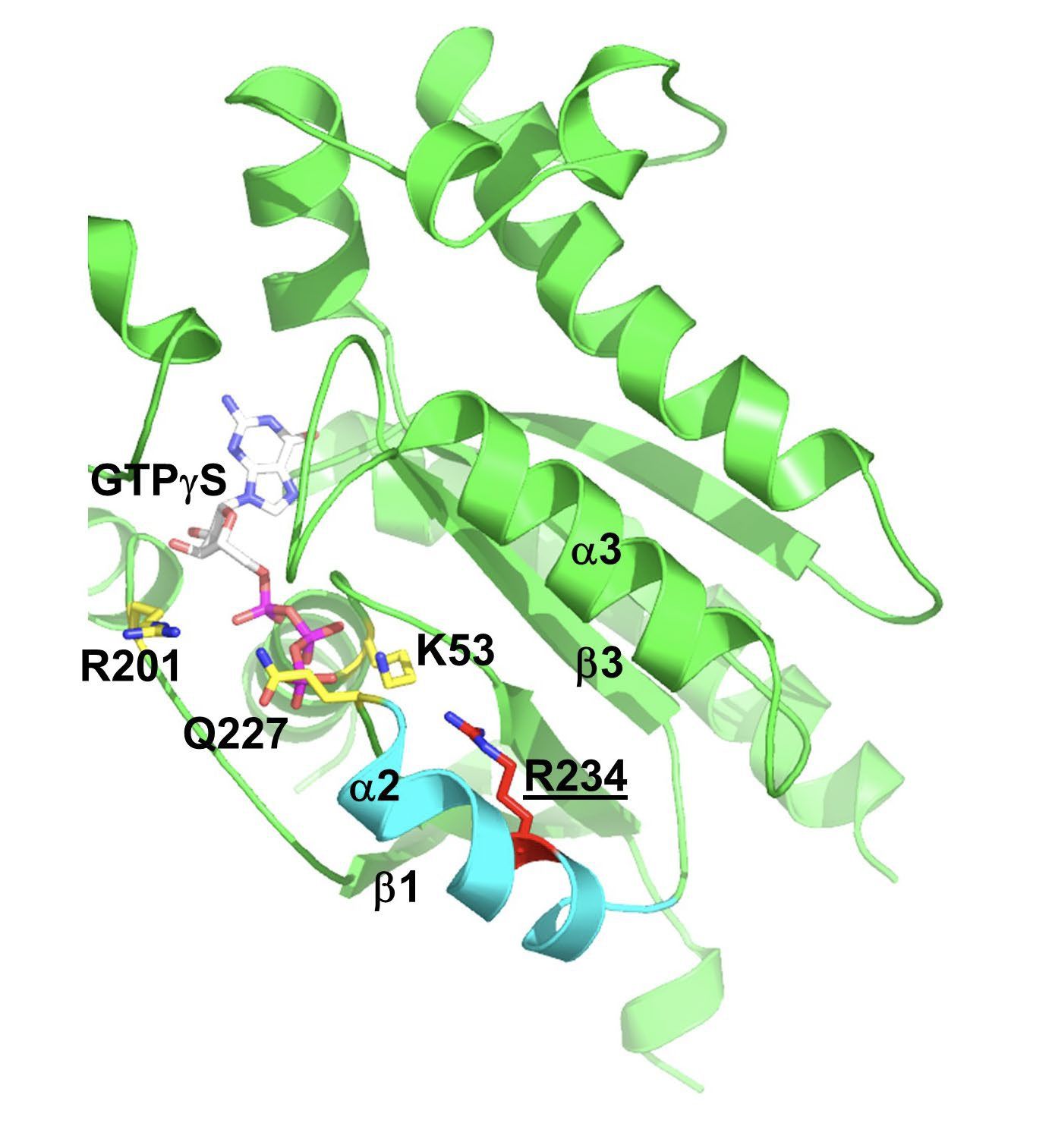

Gsα and structural modeling predicted that the W234R mutation causes GTP binding in a conformation unsuitable for hydrolysis (figure below).

Finally, whole cell patch clamp electrophysiology of mutant W234R Gsα increased L-type calcium channel current density by approximately 50%, and when this is combined with enhanced calcium current permeability from adrenergic stimulation, DADs and triggered activity were simulated in an in silico model of human ventricular myocytes. The figure below is a summary of these findings.

The laboratory is now focused on understanding the subcellular mechanisms that mediate the functional effects of the identified mutations. To that end, we are using gene editing techniques to express these mutations in induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) and differentiate them into cardiac cells in order to more fully understand calcium trafficking within the cell and the basis for this form of ventricular tachycardia.